Yazidi Survivors

Layla Taloo poses for a portrait in the full-face veil and abaya she wore while enslaved by Islamic State militants, at her home in Sharia, Iraq. Her ordeal in captivity underscores how IS members continually ignored the rules the group tried to impose on the slave system. “They explained everything as permissible. They called it Islamic law. They raped women, even young girls,” said Taloo, who was owned by eight men. (AP Photo/Maya Alleruzzo)

In August 2014, the group known as Islamic State (IS) launched an attack on the heartland of the Yazidi community at the foot of Sinjar Mountain, in northern Iraq. IS sees Yazidis as heretics and therefore a valid target for extermination, in their vision of a new caliphate ruled by Sharia law. From 2014 until US and Iraqi forces began liberating the region in 2017, a slavery economy operated in IS-held territory. In recent years, reports have emerged across the media of women and children handed out as gifts and sold as slaves, for a stipend of around US$50 per slave and US$35 per child. In May 2020, Associated Press reported that although some 3,500 slaves had been freed, most ransomed by their families, some 2,900 Yazidis remained unaccounted for. The United Nations has called the attacks an act of genocide against the minority group. The independent Commission for International Justice and Accountability (CIJA), which has been investigating IS in Iraq since 2015, has now built up a substantial body of evidence and first-hand witness accounts in order to construct case files that identify ranking IS members as responsible for atrocities, including genocide and other crimes against humanity.

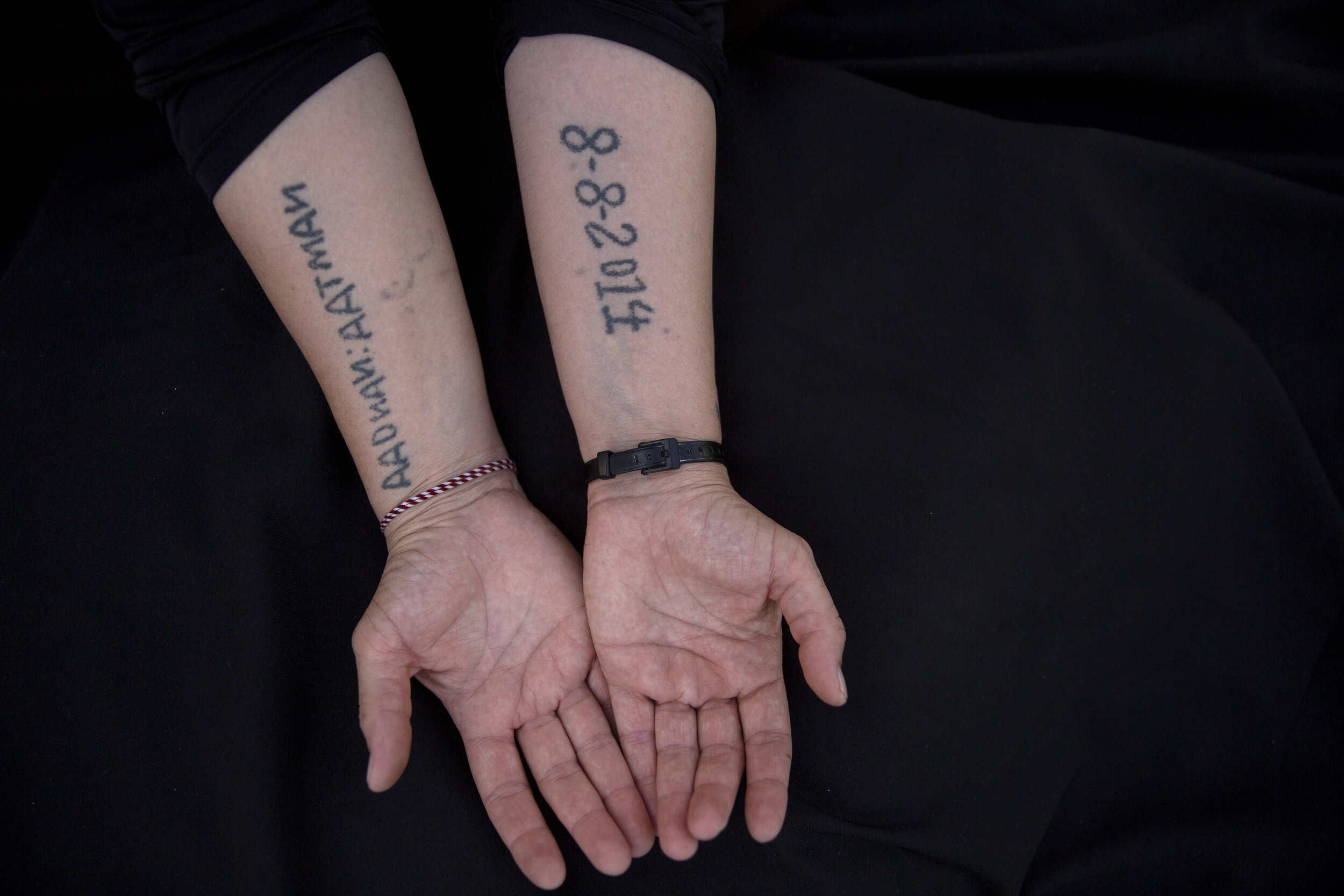

Leila Shamo displays tattoos she made while enslaved by Islamic State militants at her home near Khanke Camp, near Dohuk, Iraq. Shamo, 34, used her breast milk, charcoal ash and a needle to write the names of her husband, and two sons on the front of her hand and the inside of her right forearm: Kero, Aadnan, Aatman. On the inside of her left forearm, she wrote the date IS militants captured them all together: 8-8-2014. (AP Photo/Maya Alleruzzo)

A Yazidi woman who endured five years of captivity by Islamic State militants poses for a portrait in her home in northern Iraq. “They beat me and sold me and did everything to me,” she says. Raped by nearly a dozen owners over years of captivity, she was owned by IS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi for months before he “gifted” her to one of his aides and freed in a U.S.-led raid in May, 2019 after her escape. (AP Photo/Maya Alleruzzo)

Pictures of Yazidis slain in 2014 by Islamic State militants are found in a small room at the Lalish shrine in northern Iraq. When Yazidis were seized alive by the militants, top commanders registered them, photographed the women and children, categorized them into married, unmarried and girls, and decided where they would be sent. Initially, the thousands of captured women and children were handed out as gifts to fighters who took part in the Sinjar offensive, in line with the group’s policy on the “spoils of war.” (AP Photo/Maya Alleruzzo)

Layla Taloo visits the Ninewa Palace Hotel, where she was once brought by her Islamic State militant captor in Mosul, Iraq. She was abducted by the extremists along with her husband and children — but once her husband was taken away, Taloo was sold to an Iraqi doctor, who three days later gifted her to a friend. Despite the rules mandating sales through courts, she was thrown into a world of informal slave markets run out of homes. (AP Photo/Maya Alleruzzo)

Layla Taloo visits the house where she was held along with her husband and children after Islamic State militants captured the family in Tal Afar, Iraq in 2014. It was the last place she saw her husband. (AP Photo/Maya Alleruzzo)

Layla Taloo is overcome with grief as her brother, Khalid, leads her away from the compound where she last saw her husband in 2014 after the family was captured by Islamic State militants in Tal Afar, Iraq. Her family was taken to a village with nearly 2,000 other Yazidis forced to convert to Islam, before the men were taken away. Their bodies were never found, but they are believed to have been thrown into a nearby sinkhole. (AP Photo/Maya Alleruzzo)

Layla Taloo directs security forces digging in the garden where she buried her mobile phone and cigarettes while being held by Islamic State militants in Tal Afar, Iraq in 2014. (AP Photo/Maya Alleruzzo)

Layla Taloo visits the grave of a Yazidi woman who took her own life after she was captured by Islamic State militants in Mosul, buried on a hill overlooking the Lalish shrine in northern Iraq. (AP Photo/Maya Alleruzzo)

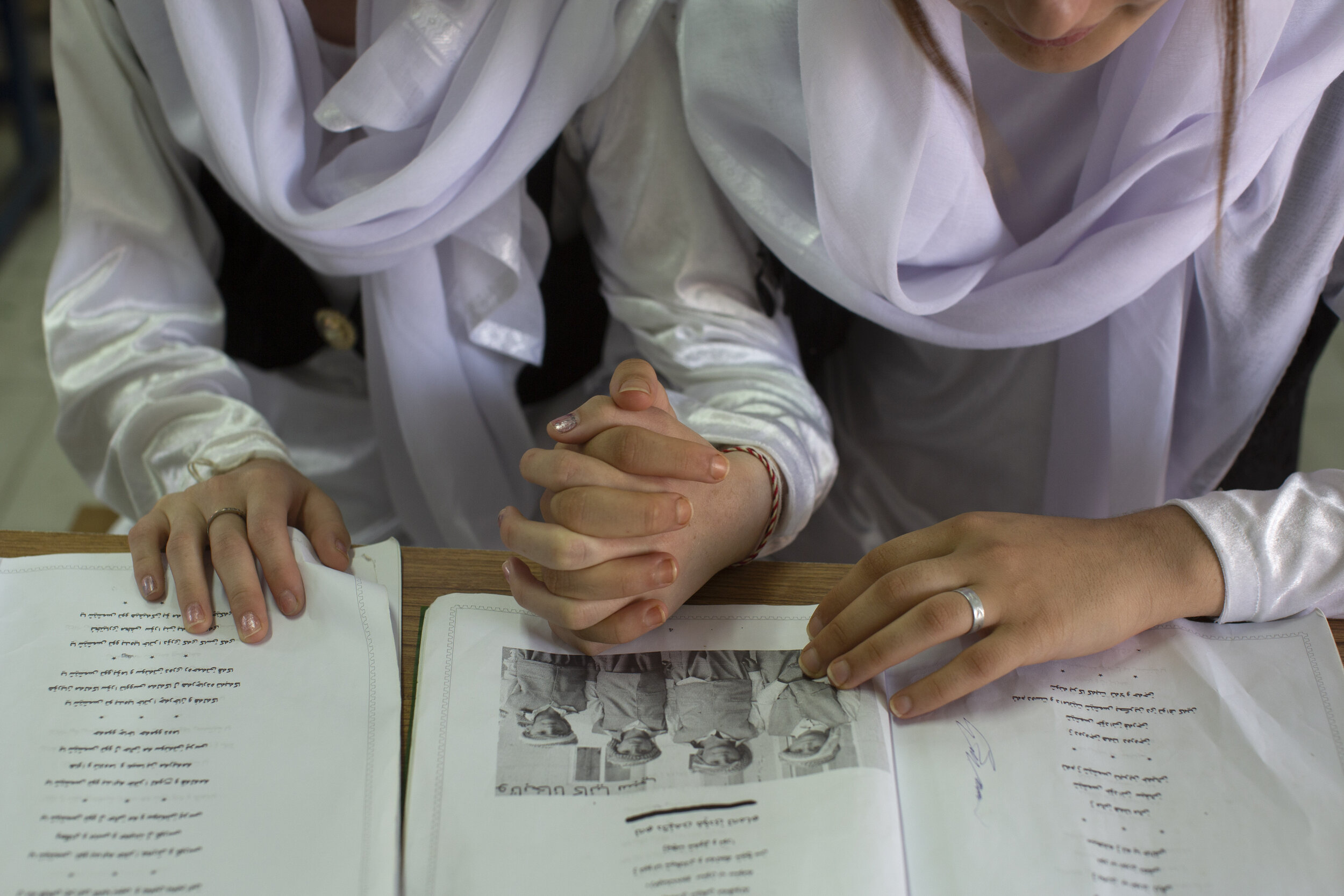

Yazidi girls, dressed in traditional clothes, take part in a program to reacquaint them with their religion and culture at Khanke IDP Camp, northern Iraq. The ancient sect is rebuilding, nearly six years after Islamic State militants launched its coordinated attack on the heartland of the Yazidi community at the foot of Sinjar Mountain in August 2014. (AP Photo/Maya Alleruzzo)

Abdul-Rahman al-Shmary, a Saudi Islamic State militant who traded in Yazidi slaves, is led byKurdish prison guards to an interview in Rmeilan, northeast Syria. He dismissed the IS rules on slavery as rooted not in Islamic law but in the leadership’s need for control. “It was about power and not for God’s sake,” he said. (AP Photo/Maya Alleruzzo)